About the Exhibit

While it appears natural, the Emerald Necklace is a dynamic and evolving work of art in the heart of Boston. Frederick Law Olmsted and his collaborators applied skill and imagination to sculpt waterways and landscapes that would uplift, re-center and secure a growing 19th-century city. In 2018, the Emerald Necklace Conservancy’s 20th Anniversary, internationally renowned artist Fujiko Nakaya continued this legacy with her unique medium: fog.

Developed to celebrate twenty years of park advocacy and to highlight both Olmsted’s and Nakaya’s ambitious work with water, the Conservancy’s Sculpting With Water exhibit highlights the Emerald Necklace’s creation, the development of Fog x FLO: Fujiko Nakaya on the Emerald Necklace and how both reconnect us to nature by design. The exhibition, housed at the Conservancy’s Shattuck Visitor Center, unites the two artists’ visions, and gives new dimension to the ideals that inspired the parks—and their conversation—into the 21st century.

Shattuck Visitor Center

125 The Fenway, Boston, MA 02115

617-522-2700

Hours

Open year-round Monday-Friday

9:30am – 5:00pm

Saturday and Sunday (May-October only):

10:00am – 4:00pm

The Creation and Function of the Emerald Necklace

Origins and Future of Green Infrastructure

Enabling A Growing Boston

In what is now called the Back Bay Fens, raw sewage once drained into Boston’s rivers and tidal estuaries, while periodic floods caused severe problems. As the city’s population increased in the 19th century, living conditions got worse. To make Boston more sanitary and safe, city engineers and Frederick Law Olmsted designed an innovative system of connected waterways that transformed the city. What we call the Emerald Necklace not only eased flooding and improved sanitation, but also allowed residents to enjoy a once-polluted part of their home.

Though Olmsted never used the term, his design of sculpted water, earth and plants is a groundbreaking example of green infrastructure. In the future, the Emerald Necklace will provide a critical buffer to nearby residents as sea levels rise and storm intensity increases due to climate change. However, as a flood control system, it functions only as well as current generations maintain it.

What is Green Infrastructure?

In most cities, the infrastructure—basic systems to move, connect and house water, power and people—are typically made of hard materials like metal and concrete. Manufactured drains (often underground) move water quickly away from streets to release it in nearby rivers, oceans, or treatment centers. Green infrastructure is different: instead of being hard, it acts more like a sponge. Using earth, stones and plants, it absorbs and treats water in place using natural systems. Those winding rivers in the parks are not just pretty—they were designed as part of a complex hydraulic system to absorb the pressure of storm water and sewage.

The Stony Brook Gatehouse

The Conservancy’s Shattuck Visitor, located at 125 the Fenway, stands above an underground river: the Stony Brook. This building once housed three gates that, when mechanically lifted or lowered, would release or hold the brook’s outflow into the Back Bay Fens. Olmsted wanted this gatehouse to both control nature and sit in harmony with it. He asked his friend Henry Hobson Richardson, architect of Trinity Church in Boston’s Copley Square, to design it using natural materials. The rough-hewn rosy Cape Ann granite structure was completed in 1882.

After the Stony Brook channel was doubled in capacity in 1905, this building was moved and an identical gatehouse was built next to it. In 1910, the Charles River was dammed at its mouth to Boston Harbor, and the Back Bay no longer experienced tides. So, the gate equipment was replaced with a pump system, which was consolidated into a single structure in 1970 and continues to operate in the building next door.

Water in Boston

This 1857 photograph shows the Back Bay on the left, before the tidal marsh became solid land. Beacon Hill is in the foreground, and the road crossing the water is Beacon Street. Source: Boston Public Library Print Department, Boston Pictorial Archive.

Boston was once a much wetter place. The Charles River was then an estuary, a river which experiences daily tides, and the area surrounding you–known as the Back Bay–was an extensive wetland. In the 19th century, developers filled in this and other sections of the city to provide land for housing and industry. As buildings sprung up atop Boston’s former salt marshes, new problems emerged.

“The environment that people live in is the environment that they learn to live in, respond to, and perpetuate. If the environment is good, so be it. But if it is poor, so is the quality of life within it.”

—Ellen Swallow Richards (1842-1911): First female graduate of MIT; Pioneer in public health

In the 1870s, the Board of Health used “odor maps” and one of the worst areas was the Back Bay, which received large amounts of raw sewage from Boston and Brookline. While the tides washed some effluent away, much remained, making the area particularly unpleasant and unhealthy. The Emerald Necklace makes Boston less smelly and more safe by treating polluted water—and managing floods.

This 1878 Board of Health map shows “the Sources of some of the Offensive Odors perceived in Boston.” The red areas are the smelliest ones, and the Back Bay, at the middle left, was a major offender! Source: Boston City Archives

There is an extensive watershed (area of drainage) that releases into the Back Bay. Olmsted designed the Fens to serve as a storage basin for floodwaters. However, as more and more surfaces were filled and paved into the 20th century, less water was absorbed naturally and instead inundated downstream areas. Boston’s developers began to forget the role, and designer, of the parks.

Remembering Olmsted’s Legacy in Boston

Olmsted in 1860, on the eve of the Civil War. Passionately anti-slavery, Olmsted aided the Union by serving on the U.S. Sanitary Commission, dedicated to improving soldiers’ health. Courtesy of the National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site

When Frederick Law Olmsted began working on the Back Bay Fens in the 1870s, he was the most renowned landscape architect in the nation, having earlier designed and supervised construction of Central Park with Calvert Vaux. While in demand across the continent, he chose Boston. Here, he applied a lifetime’s worth of experience to the design of much more than a park, but a system of interconnected greenspaces that combined recreational uses, environmental engineering and flood control.

Though Olmsted’s design philosophy was based in 18th-century British ideas, his process was cutting-edge. Ultimately, Olmsted and Boston transformed each other. By the time he retired in 1895, he gave the region one of the nation’s finest park systems, and it became the home for his family and the very first landscape architecture firm in North America.

Olmsted the Innovator

Turning a polluted tidal flat into a serene park and innovative flood-control system did not happen quickly. While he worked on designs prior, Olmsted submitted his first plan in 1879, and completed construction by 1895. To improve water flow, a dredge scooped sediment to clear deeper channels. This required steam-powered equipment set on barges—advanced technology for the time.

Olmsted carefully documented the landscapes he was working on, and embraced new technologies that made his work more effective and precise. This included new steam-powered earth-moving equipment—and the camera! He not only thought to record sites for designs, but here he captured members of his team in action, photographing Franklin Park—a document not just of the landscape, but of the work of landscape architecture.

Green Infrastructure: Past and Present

Each generation leaves its imprint on the Emerald Necklace, and nowhere is this more evident than on the Muddy River, which connects Jamaica Pond to the Charles River. In the late 19th century, Olmsted transformed this fouled brook into an idyllic stream that meanders through curving, tree-lined banks. By the 1920s, though, automobiles had taken over Boston. In the mid-20th century, the city paved over a large section of the Muddy River to provide parking for a location of the Sears, Roebuck & Company.

A later generation decided they wanted the Muddy River back. Severe flooding and other issues prompted concerned citizens and officials to found the Emerald Necklace Conservancy in 1998 in order to advocate for and safeguard this park system. Starting in 2000, the Conservancy worked with a coalition of residents and government agencies to “daylight” the covered portion of the Muddy River and improve water flow and quality. By 2017, six decades since covered, the Muddy River flows outside under open skies once again in a section of the Necklace rededicated as the Justine Mee Liff Park.

“We want a ground to which people may easily go after their day’s work is done, where they may stroll for an hour, seeing, hearing, and feeling nothing of the bustle and jar of the streets.”

– Frederick Law Olmsted, 1870

Making Connections: The Whole is Greater than the Sum of its Parts

The Emerald Necklace is a connector: it joins parts of the city, links natural ecosystems, and engages people with each other and nature. Olmsted described it as “public ways, adapted to pleasure travel, … provided for connecting the several pleasure grounds.” It was a length of greenspace that allowed easy access and continuous transit through nature from park to park, to escape the pace of the city without ever having to leave it.

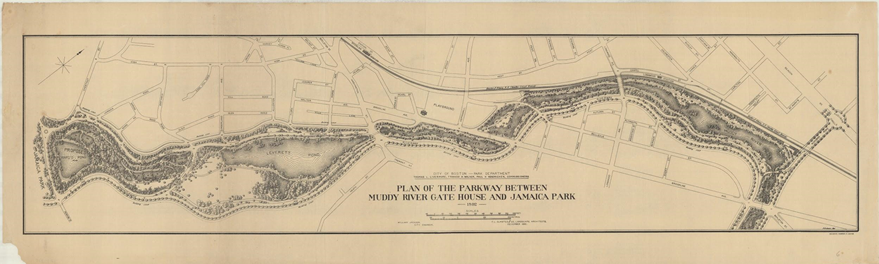

As Olmsted’s 1892 plan for the Muddy River Improvement shows, these parks form a unified whole – a sinuous green oasis that weaves through the city. Though streets always intersected these spaces, Olmsted often designed tunnels or other crossings to ensure that visitors could experience the parks as a continuous landscape. Courtesy of the National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

When one part of the park network is broken, the whole does not function properly. So the Emerald Necklace Conservancy is committed to working with partners and residents to rebuild important connections. One example is the removal of the Casey Overpass along the Arborway. There, a pedestrian-level parkway with green infrastructure elements has replaced a car-only highway overpass.

In the mid-1950s, the Casey Overpass was constructed for high-speed car traffic over the Arborway, a tree-lined parkway that linked Arnold Arboretum and Franklin Park. In 2010, the Department of Transportation worked with community groups to improve traffic patterns, make the route more pedestrian and bicycle friendly and incorporate green infrastructure. Concluding in 2018, this project is one of several that that links the Emerald Necklace back together as Olmsted intended. Source: MassDOT

Parkways and Franklin Park

In 1876, Boston’s Park Commissioner Charles Dalton submitted a report detailing the need for more green spaces in the city. This system was the prototype for Olmsted’s later work.

More Than a Park, Better Than a Road:

Parkways and the Growing City

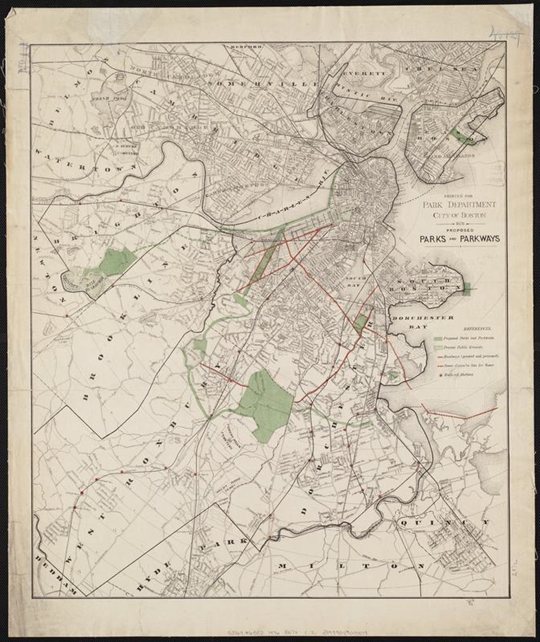

Olmsted shaped both fluid landscapes and the flowing movement of pedestrians and vehicles. As Boston expanded, roads became congested and open space diminished. City officials hoped a series of interconnected parks, like the one depicted in this 1876 map, would help ease these growing pains.

As the 1887 plan for the Back Bay Fens shows, Olmsted’s vision was curving, not straight edged—weaving nature into the urban fabric more seamlessly. When the tree-covered parkways encircled the city in subtle turns and slopes, they revealed views around each bend, making travel through Boston pleasant and inspirational. Along these roads, Olmsted included carriage stops, an innovation that allowed riders to pause and walk around the parks. In the 20th century, these were renamed “parking spots.”

Once Olmsted was formally brought on as a designer, he refined earlier visions. This map from 1887 shows finalized plans for the Back Bay Fens and, in the upper left corner, how this park fits into a larger network. 1876 and 1887 map reproductions courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library.

Franklin Park: The Emerald Necklace’s “Crown Jewel”

Franklin Park was dedicated to the “quiet enjoyment of natural scenery.” The 1885 plan included over 500 acres of rolling hills, sweeping meadows and serene woods. While passive recreation was paramount, Olmsted included sections to accommodate more active uses.

Olmsted believed pastoral scenery could relieve industrialization and urbanization’s damaging effects on city dwellers. Landscapes like Franklin Park’s Nazingdale could improve urban residents’ physical and psychological well-being by providing fresh air, space for recreation, and places for peaceful contemplation.

(L): Olmsted’s 1885 plan not only mapped out the park’s design, but also its underlying philosophies and functions. Within a single park, he included a wide range of spaces that accommodated many uses. At right is The Greeting – a never-built promenade intended for socializing. (R): This view of Franklin Park embodies a “pastoral” landscape central to Olmsted’s designs. He wrote that the pastoral “consists of combinations of trees, standing singly or in groups, and casting their shadows over broad stretches of turf, or repeating their beauty by reflection upon the calm surface of pools, and the predominant associations are in the highest degree tranquilizing and grateful…” Both images courtesy of the National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

A Visionary: Thinking Ahead

Olmsted was not only in tune with nature, but also society. The decade before relocating here in 1881, Olmsted frequently spoke to Boston’s civic planners, real estate developers and intellectual leaders to build allies for a future city. Rather than monotonous and inflexible grids, he championed varied greenspaces that promoted different cultural functions. As the growth was accelerating, he had the foresight to eloquently and forcefully advocate for the democratic ideals and long-term importance of urban parks.

(L-R): 1: Olmsted warned against the uniform straight lines that were guiding planning to fill this site. 2, 3: Instead he preserved greenspace that remains in the face of ongoing urban development. 4, 5: Some of the edges were smoothed by Arthur Shurcliff in the 1920s after the damming of the Charles River. Images courtesy Atlas of the county of Suffolk, Massachusetts, vol 1: Including Boston Proper, GM Hopkins & Co., 1874; Atlas of the City of Boston: Boston Proper and Back Bay. Map. Philadelphia: G.W. Bromley and Company, 1908, 1917, 1928 and 1938 editions.

“It is practically certain that the Boston of today is a mere nucleus of the Boston that is to be.”

—Frederick Law Olmsted (1870)

Isabella Stewart Gardner purchased land near the Fens by 1901 to build her Palazzo, opened as a museum on New Year’s Day in 1903. Simmons College purchased a plot of neighboring land in 1903 to open their first main building by 1904. Atlas of the City of Boston: Boston Proper and Back Bay. Philadelphia: G.W. Bromley and Company, 1908.

Olmsted’s vision ultimately inspired Boston’s cultural center. The Back Bay Fens became a magnet for institutions of arts and learning. Isabella Stewart Gardner chose to build her palazzo at the other end of the Fens, and open it as a public museum named “Fenway Court” in 1903. By 1907, the Museum of Fine Arts relocated from Copley Square, and in 1912 Fenway Park became home to the Boston Red Sox, while numerous colleges were established here in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Designing in and For Nature: “Genius of Place” and Olmsted’s Artistry

Olmsted envisioned the Emerald Necklace as a unified composition rather than a collection of separate parks. From small paths to entire views, Olmsted collaborated with a wide range of architects and planners in carefully designing every aspect of this park system. Throughout the Emerald Necklace, Olmsted sought to express the “genius of the place:” the cumulative effect of a landscape’s inherent qualities that should be respected and emphasized in all design work. Thus, all the plantings and structures in Boston’s parks had to harmonize with the natural setting.

In the plan for the Muddy River Improvement, Olmsted detailed the exact location for dozens of plant species. Olmsted worked closely with Charles Sprague Sargent, first director of Arnold Arboretum, on choosing plant materials and designs. Courtesy of the National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site

Fujiko Nakaya and Sculpting with Fog

Dialogue Across Generations

“What artist, so noble … as he who with far-reaching conception of beauty and designing power, sketches the outlines, writes the colors, and directs the shadows of a picture so great that Nature shall be employed upon it for generations…”

– Fredrick Law Olmsted, 1852

“I’m driven by the feeling of being absorbed in nature.”

–Fujiko Nakaya, 2017

Both Fujiko Nakaya and Frederick Law Olmsted are innovative artists who combine scientific observation and creative imagination to craft immersive artworks. Instead of seeing boundaries between different realms of knowledge, they integrate insights from a range of sources and disciplines.

(L): Courtesy of the National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site; (R): Courtesy Jen Mergel

Olmsted’s Origins

In 1883, Olmsted moved to Fairsted with his wife Mary and their children. Courtesy: National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

Born in 1822 in Hartford, Connecticut, Olmsted grew up exploring the nearby countryside and gained a love for rural scenery. Before coming to Boston, his life took many twists and turns. He sailed to China on a merchant ship, managed farms, oversaw a California gold mine, and was an accomplished and prolific writer who published popular essays about his travels in England and the Southern United States. During the Civil War, he headed the U.S. Sanitary Commission, predecessor to the American Red Cross, and campaigned to protect Niagara Falls and preserve what is now Yosemite National Park. Through these experiences, Olmsted gained a deep appreciation for nature’s ability to heal and bring people together. He integrated his social, aesthetic and engineering concerns into a new profession he called “landscape architecture.” In the Emerald Necklace, these beliefs found full expression.

Nakaya’s Origins

Nakaya’s father, Ukichiro Nakaya (1900-1962), was a pioneering scientist who studied the process of crystallization and created the first artificial snowflakes in a laboratory. Born in Sapporo, Japan, in 1933, Fujiko Nakaya moved with her family after WWII to Chicago. After high school there, she studied art at Northwestern University, then painting at the Sorbonne in Paris. By the 1960s, she was painting clouds but eager to create art: not as fixed compositions but as fluid, evolving forms that would naturally compose and decompose in real time—like clouds. She returned to Japan and since 1969 has pioneered a unique form of dynamic, engaging, site-responsive art aptly described as “fog sculpture.” Through her collaborations with the American group Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.)—in particular with artists Robert Rauschenberg, engineer Billy Kluver, and cloud physicist Thomas Mee—she honed designs of her fog art nozzle systems by 1969—and patented the system for fog art in 1989.

Nakaya’s fog sculptures have been shown over 80 times around the world in a range of environments, from Australian deserts and Japanese gardens, to meadows in France and the San Francisco Bay, from the National Mall in Washington, D.C. to a parking garage in Austria, and at the exteriors of museums including the Guggenheim Bilbao, the Toyota Municipal Museum, the Tate Modern in London and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. This exhibition of five simultaneous installations across 5 miles of parks in Boston is her most extensive and expansive exhibition in her 50 year career.

How Do You Make Fog?

Nakaya developed her fog production system through careful, time-consuming research and experimentation. Unlike fog machines, which use artificial chemicals, Nakaya’s system uses pure water. Even before the Earth Day and environmentalist movement began, she wanted to create an experience that was as safe as nature for people, and all species, to enjoy. She worked with physicists and engineers to determine how to create extremely fine water vapor (smaller than droplets in mist or rain). By 1970, she debuted her first sculpture, and timed the ultra-fine mists to release at intervals to respond to a location’s wind patterns, temperature, and humidity–making visible all of those unseen forces that shape how we feel about a place.

The resulting hydraulic system turns a continuous flow of water into millions of individual particles. High-pressure pumps expel water through a 16 micron diameter nozzle after which it immediately hits a needle that shatters the water into 20-30 micron-sized water droplets – the same in natural fog. Today, Nakaya uses 3D modeling and a sophisticated computer system to choreograph the sequenced movement of fog, but the mechanics are still the same as they were in 1969.

Fog x FLO: Fujiko Nakaya on the Emerald Necklace

Fog x FLO: Fujiko Nakaya on the Emerald Necklace

For the Conservancy’s 20th Anniversary, Nakaya responded to sites designed by Frederick Law Olmsted (FLO) to present her most extensive citywide exhibition to date, Fog x FLO: Fujiko Nakaya on the Emerald Necklace. The sites were paced to encourage visitors to travel from one site to the next—she calls them “stepping stones” to follow and (re)discover the parks.

Five works marked her five-decade career and the various ways she has presented fog in dialogue with different forms: from immersive installations that fall from tree canopies, to picturesque scenes on water surfaces, from interactions with the steep hills or bowls carved of the landscape to dialogues with structures built by renowned architects. Here are just a few of her works in detail:

Fog x Ruins (#72509_Franklin Park Overlook)

Olmsted designed Franklin Park’s Playstead to give Bostonians a site for recreation, relaxation, and celebration. In the 1890s, people prepared for and watched sports and other events at the nearby Overlook Shelter. Then the shelter burnt down. In the 1960s, the site hosted popular concerts, including several by Duke Ellington. Nakaya hopes to reanimate this Olmsted-designed building, which now lies in ruins with a fog structure that “dances” around us.

Like Olmsted’s Shelter (left), Nakaya’s work (right) is intimately bound with its environment and climate. In the Shelter’s design, Olmsted incorporated Roxbury puddingstone–a rock formation unique to the Boston area that reveals the region’s layered geological past. Nakaya’s fog, which envelops the Shelter’s ruins, likewise evokes ghosts of the region’s cultural past. Sources: L: Courtesy of the National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Park Service; R: Fujiko Nakaya | Processart Inc.

Fog X Island (#72509_Leverett Pond)

At Leverett Pond, Nakaya and Olmsted collaborate across a century. Her fog sculptures emerge from a row of small islands and drift out over Leverett Pond. In the 1890s, Olmsted reshaped both these islands and the pond’s shores. Olmsted had a keen sense of how to heighten the visual effect of ponds and streams while also improving their flow. Throughout Nakaya’s career, she has studied water’s complex transitions between different states of matter.

Left: This 1890s plan for Leverett Park (now called Olmsted Park) shows the pond as well as an area that was originally intended to have educational “natural history pools” that would showcase aquatic plants, animals and birds. Right: Nakaya’s Leverett Pond fog sculpture uses Olmsted’s landscape as a pedestal to reach out into the body of water. Sources: L: Courtesy of the National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site; R: Fujiko Nakaya | Processart Inc.

Fog x Canopy (#72509_Fens)

Olmsted and Nakaya both want you to experience the unexpected wonder of an unfolding journey.

Throughout the Emerald Necklace, Olmsted carefully laid out paths to draw our attention to how views develop as we move through time and space. Across the Muddy River a short walk from where you’re standing, a curved path through tall plane trees, lets you view their majestic forms in a progression. Nakaya’s fog sculptures emerge from these tree’s canopies, creating a new atmosphere to this passage—a new part of the journey for us to encounter.

Left: In this sketch of Back Bay Fens, Olmsted lays out the original circulation patterns for water and people. What changes do you see in the landscape since Arthur Shurcliff redesigned the Back Bay Fens after the Charles River was dammed? Right: Nakaya’s tree canopy installation creates a “fog corridor,” a new way to experience movement through the Back Bay Fens. Source: L: Courtesy of the National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site; R: Fujiko Nakaya | Processart Inc.